MARITIME TRADITIONS

From the time of its earliest settlement in the 18th century, North Haven’s cash economy depended on the success of the fishing industry. While farming was certainly of importance for nearly all of the island’s residents, it was fishing that brought early prosperity to the island. Even during the days of its early settlement, North Haven was home to a good number of deep water mariners, boat and ship builders as well as numerous fishermen who worked on coasters and seiners. Fishermen sometimes left the island for months at a time but upon their return they brought much needed cash to supplement the livings that their families made as farmers.

Many of the earliest settlers were able to build the boats and ships they needed for coastal trade, for fishing and for daily use getting from one part of the island to another. The Kents, the Watermans, many members of the Ames and Cooper families and the Dyer, Crabtree, Hopkins and Thomas families and others were listed as shipbuilders in early census reports.

Schooners were built here as early as 1795 when Eleazar Crabtree built the 137 ton, 74 foot LUCY. A few years later, near his home at the head of Southern Harbor, he built a full-rigged ship the LUCY AND NANCY. This latter ship was lost off the coast of Ireland though Capt. Crabtree and his crew were rescued and landed in Liverpool.

The building of such large vessels within a relatively few years after the permanent settlement of the islands is remarkable and indicates a healthy supply of labor, plentiful timber, tidal powered saw mills and a thriving series of stores and businesses to supply the sails, barrels and other equipment necessary for the fishing industry. Even knitting nets for the fishing industry became an extensive home industry carried on year round. It employed over 100 people, including many women and children.

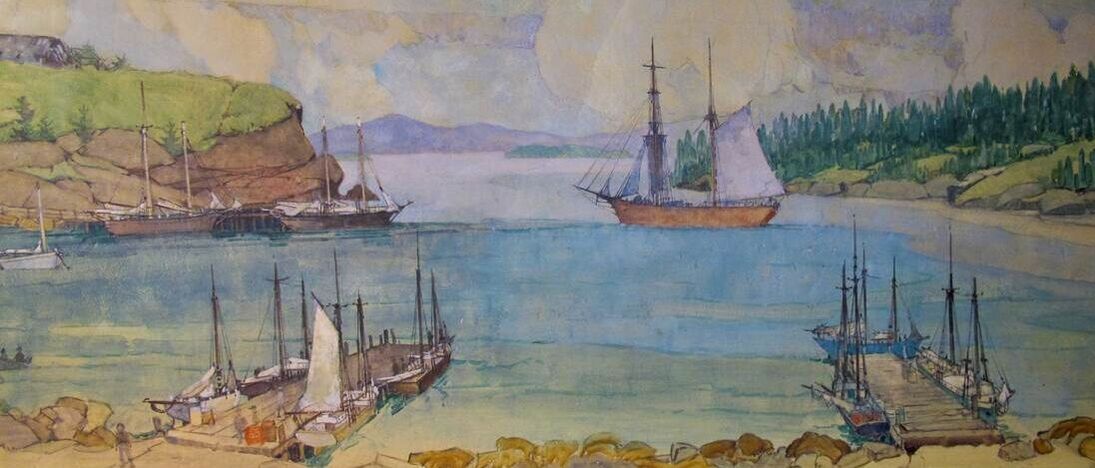

The larger vessels built on North Haven were intended primarily for fishing and West Indies trade, though many were also used for the carrying trade at a time when the sea was the great highway and travel by water was considerably simpler and less expensive than travel by land. THE GOLDEN CLOUD, built at North Haven in 1853 was described in a Rockland newspaper as a ship “intended for the Grand Banks in the summer and the West Indies trade in the winter.” This would have been an accurate description of many of the ships built here. Streams of schooners, two and three-masted, sailed through the Thoroughfare daily. Though diminished, this traffic reflecting the prosperity of the mid-coast region of Maine, lasted through the first two or three decades of the 20th century.

Boats and ships were built in many of the coves and small harbors on North Haven especially at Pulpit Harbor, Bartlett’s Harbor, the Little Thoroughfare and the area on the Thoroughfare that is now the village of North Haven. Evidence of local prosperity based in ship building, fishing and coastal trade still survives in several Greek revival residences on Main Street.

Many of the earliest settlers were able to build the boats and ships they needed for coastal trade, for fishing and for daily use getting from one part of the island to another. The Kents, the Watermans, many members of the Ames and Cooper families and the Dyer, Crabtree, Hopkins and Thomas families and others were listed as shipbuilders in early census reports.

Schooners were built here as early as 1795 when Eleazar Crabtree built the 137 ton, 74 foot LUCY. A few years later, near his home at the head of Southern Harbor, he built a full-rigged ship the LUCY AND NANCY. This latter ship was lost off the coast of Ireland though Capt. Crabtree and his crew were rescued and landed in Liverpool.

The building of such large vessels within a relatively few years after the permanent settlement of the islands is remarkable and indicates a healthy supply of labor, plentiful timber, tidal powered saw mills and a thriving series of stores and businesses to supply the sails, barrels and other equipment necessary for the fishing industry. Even knitting nets for the fishing industry became an extensive home industry carried on year round. It employed over 100 people, including many women and children.

The larger vessels built on North Haven were intended primarily for fishing and West Indies trade, though many were also used for the carrying trade at a time when the sea was the great highway and travel by water was considerably simpler and less expensive than travel by land. THE GOLDEN CLOUD, built at North Haven in 1853 was described in a Rockland newspaper as a ship “intended for the Grand Banks in the summer and the West Indies trade in the winter.” This would have been an accurate description of many of the ships built here. Streams of schooners, two and three-masted, sailed through the Thoroughfare daily. Though diminished, this traffic reflecting the prosperity of the mid-coast region of Maine, lasted through the first two or three decades of the 20th century.

Boats and ships were built in many of the coves and small harbors on North Haven especially at Pulpit Harbor, Bartlett’s Harbor, the Little Thoroughfare and the area on the Thoroughfare that is now the village of North Haven. Evidence of local prosperity based in ship building, fishing and coastal trade still survives in several Greek revival residences on Main Street.

As early as 1820, North Haven and Vinalhaven owned 700 tons of fishing vessels. By 1879, North Haven had 26 vessels, six of which were devoted to the mackerel fisheries. Three fished primarily for cod in the Grand Banks while the remaining eleven stayed closer to home to bring in cod, haddock, pollack, hake, mackerel and herring.

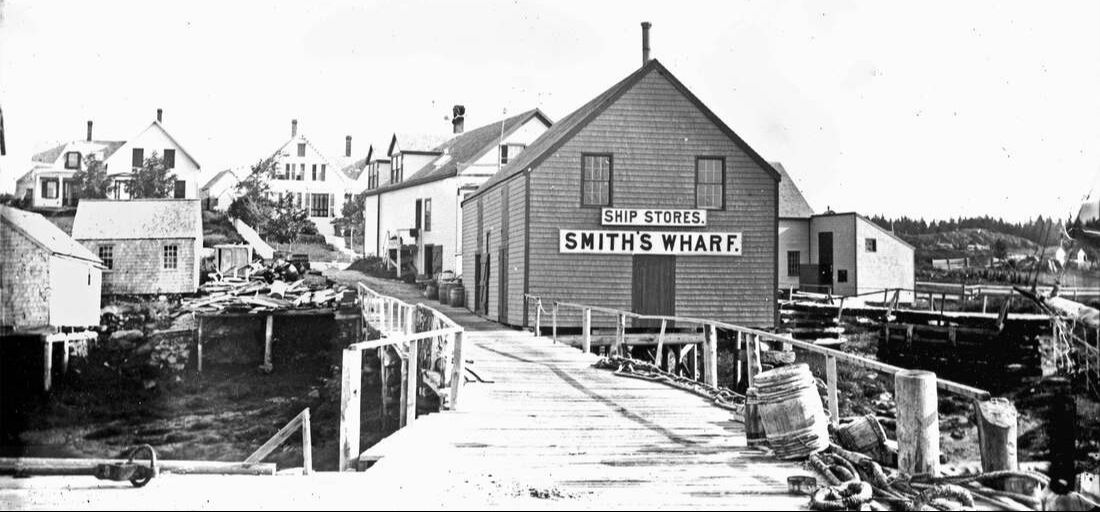

In the 19th century, the local residents who were the most prosperous were often merchants like Freeman H. Smith (married to Etta Cooper), who owned a general store and a ship’s chandlery as well as a number of schooners. Smith, whose store stood where Waterman’s Community Center now stands, was a prominent North Haven citizen who prospered through his involvement in the fishing industry. His store fitted out vessels going to sea and Smith himself owned all or a significant share of at least five large seiners. His home is the Greek revival house now owned by David and Roberta Cooper.

The early prosperity reflected in homes such as Freeman Smith’s declined after the Civil War when the U.S. government eliminated the bounty it had paid on cod. This was a serious blow to the Grand Banks fishermen. Additionally, in the late 19th century, the fishing industry in Penobscot Bay went into a deep and sudden decline. The local economy was traumatically affected. The canning factory in downtown North Haven closed and the government imposed a moratorium on the spring mackerel season. By 1887, conditions on the island were reported in the Rockland Opinion:

Vessels that had been fishing for eight months had not even wet their seine nets…the conditions of these men and their families through the coming winter can hardly be imagined…

Coincidentally, at almost this exact moment in history, wealthy Bostonians began to purchase farms and open land on North Haven for summer cottages. Within a few decades, North Haven sustained a growing population of summer “rusticators” who valued the beauty and privacy offered by the island. Their economic and social investment in North Haven altered much of the local economy and provided livelihoods for many families.

In the 19th century, the local residents who were the most prosperous were often merchants like Freeman H. Smith (married to Etta Cooper), who owned a general store and a ship’s chandlery as well as a number of schooners. Smith, whose store stood where Waterman’s Community Center now stands, was a prominent North Haven citizen who prospered through his involvement in the fishing industry. His store fitted out vessels going to sea and Smith himself owned all or a significant share of at least five large seiners. His home is the Greek revival house now owned by David and Roberta Cooper.

The early prosperity reflected in homes such as Freeman Smith’s declined after the Civil War when the U.S. government eliminated the bounty it had paid on cod. This was a serious blow to the Grand Banks fishermen. Additionally, in the late 19th century, the fishing industry in Penobscot Bay went into a deep and sudden decline. The local economy was traumatically affected. The canning factory in downtown North Haven closed and the government imposed a moratorium on the spring mackerel season. By 1887, conditions on the island were reported in the Rockland Opinion:

Vessels that had been fishing for eight months had not even wet their seine nets…the conditions of these men and their families through the coming winter can hardly be imagined…

Coincidentally, at almost this exact moment in history, wealthy Bostonians began to purchase farms and open land on North Haven for summer cottages. Within a few decades, North Haven sustained a growing population of summer “rusticators” who valued the beauty and privacy offered by the island. Their economic and social investment in North Haven altered much of the local economy and provided livelihoods for many families.

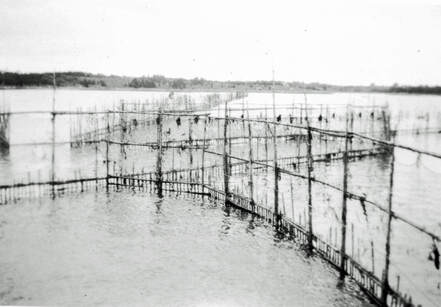

Nonetheless, fishing in many forms continued. In an interview in 1988, Irven Stone recalled the many weirs that were set up in the coves and small harbors around the island. He indicated that the best years in the 20th century for weir fishermen were 1918 and 1919. His father, Hiram Stone, maintained three weirs; in Kents’ Cove, Alex Gillis and Leigh Witherspoon kept a weir; Owie Gillis and Will Calderwood together maintained a weir as did Phil Brown, Owen Quinn and Ernest Brown. Al Ames and Will Brown also had a weir in Southern Harbor. Irven recalled that his father kept a huge tar pot on the shore. The tar was used for coating all of his father’s twine nets. “When there were any herring around, this was a very good weir”, said Stone.

Men in two dories thumped their oars on the sides of their boats to herd fish into the weirs. The fish would be removed by dip net or pumped into a waiting smack. The men used long poles of very thin wood to feel the depth of fish in the weir. If there were only a few, they were taken right into the dory for use as lobster bait.

In discussing the various forms of fishing undertaken by North Haven fishermen in the 20th century, Stone mentions that many of the fishermen kept two homes, one, in-town, for the winter and another, more of a camp, used for summer fishing. Lobstering, scalloping, using weirs for herring and also going after smelts were seasonal occupations for North Haven fishermen. Stone maintains that “up to Zion” was the most successful place to fish for smelts in the winter:

Eight or so dories with two men in each would go over to Zion with ice saws. They would saw big cakes out of the ice, push them out to open water and let the tide take them away. Having made a large space of open water in the ice, the men would set their nets. Most often they would catch lots of smelts hiding in the eel grass under the ice.

The smelts were packed into wooden boxes at Ed Mills’ fish market, shipped out by the evening and arrived fresh in Boston by the next morning. Finally, Stone closes his interview:

I can see those men now as they left the dock, yellow oilskins, rubber boots and long white woolen mittens. After a day the wool would shrink to just fit the hand. Those men are now all gone, and most forgotten.

Today, two or three men or women to a boat, fishing for lobster is a crucial part of the economy of North Haven. Nowadays over 40 lobster boats set sail from North Haven each season. Together they provide a living for 80 to 90 residents and their families.

Men in two dories thumped their oars on the sides of their boats to herd fish into the weirs. The fish would be removed by dip net or pumped into a waiting smack. The men used long poles of very thin wood to feel the depth of fish in the weir. If there were only a few, they were taken right into the dory for use as lobster bait.

In discussing the various forms of fishing undertaken by North Haven fishermen in the 20th century, Stone mentions that many of the fishermen kept two homes, one, in-town, for the winter and another, more of a camp, used for summer fishing. Lobstering, scalloping, using weirs for herring and also going after smelts were seasonal occupations for North Haven fishermen. Stone maintains that “up to Zion” was the most successful place to fish for smelts in the winter:

Eight or so dories with two men in each would go over to Zion with ice saws. They would saw big cakes out of the ice, push them out to open water and let the tide take them away. Having made a large space of open water in the ice, the men would set their nets. Most often they would catch lots of smelts hiding in the eel grass under the ice.

The smelts were packed into wooden boxes at Ed Mills’ fish market, shipped out by the evening and arrived fresh in Boston by the next morning. Finally, Stone closes his interview:

I can see those men now as they left the dock, yellow oilskins, rubber boots and long white woolen mittens. After a day the wool would shrink to just fit the hand. Those men are now all gone, and most forgotten.

Today, two or three men or women to a boat, fishing for lobster is a crucial part of the economy of North Haven. Nowadays over 40 lobster boats set sail from North Haven each season. Together they provide a living for 80 to 90 residents and their families.