ONE ROOM FOR ALL*

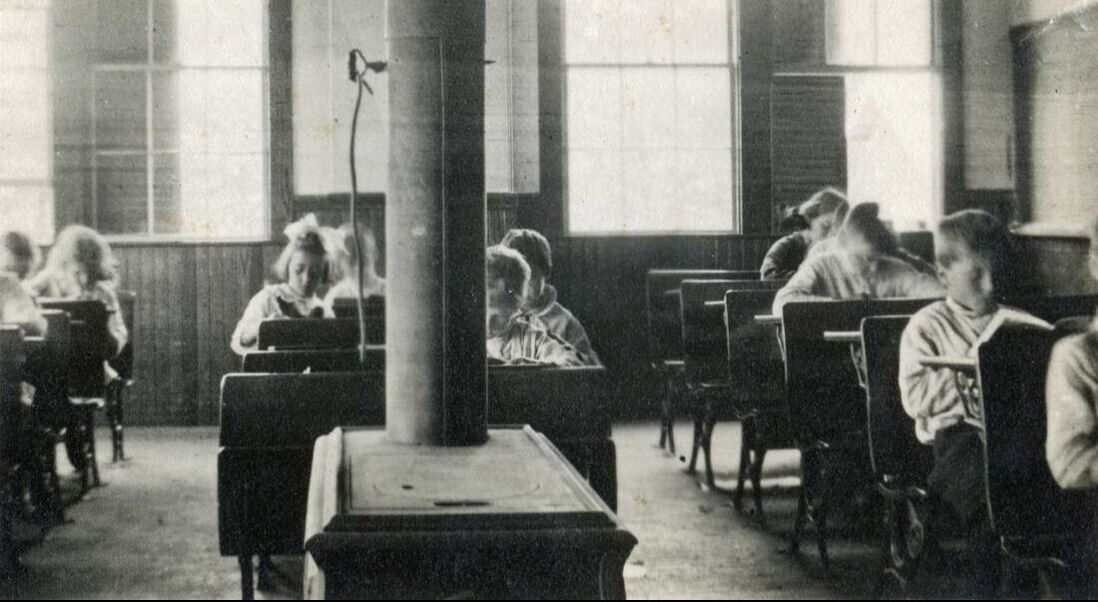

School children in the early 1900s didn’t have the conveniences that today’s children have…No steady heat day and night -- a fire was built every morning by the teacher or by one of the pupils who was hired to do the janitor work. Since it took some time to heat the back of the room, the children were allowed to sit by the stove until the room warmed up some. No electric lights to turn on [during] dark days to make the room more cheerful as well as furnishing more light.

Nettie Beverage Crockett, Personal recollection, 1966

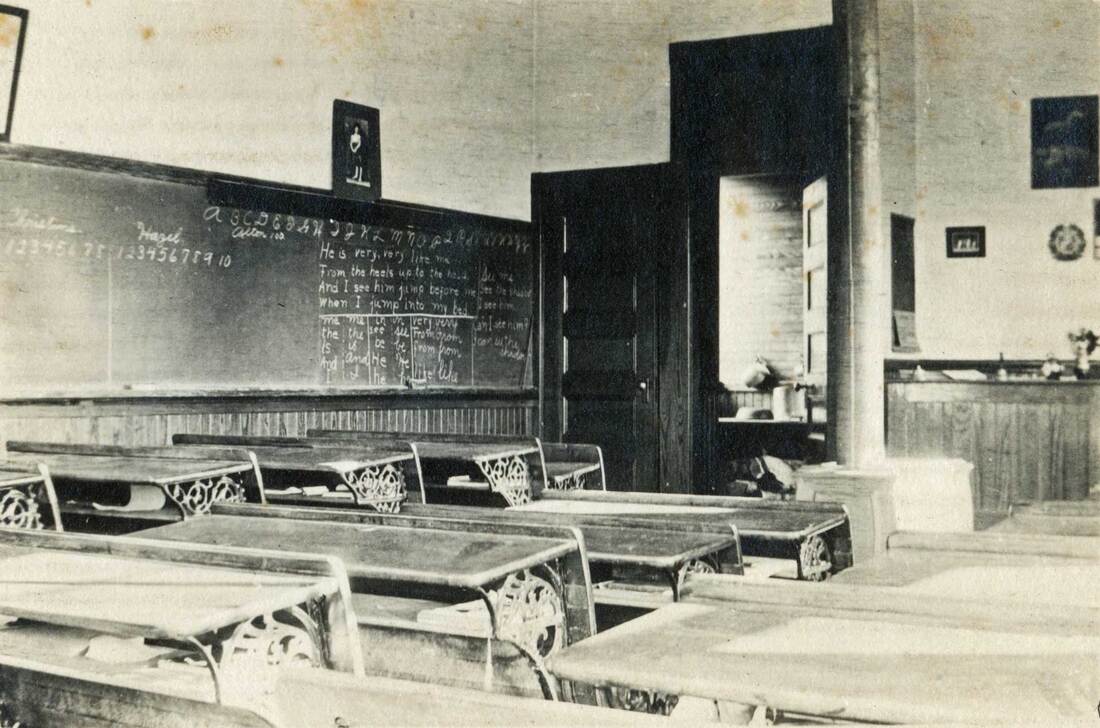

Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, school houses on North Haven were simple, one-room, single-story buildings, without electricity, plumbing, or central heat. A stove, fueled with wood from the pile outside, provided heat and students fetched drinking water from a local spring or well.

There was no sink, no water pipes, but we always had a water pail set out on the bench there, and there was a big dipper there that everybody drank out of.

Winnie Burgess Ames, Interview with Eliot Beveridge, circa 1980

The water supply came from Mr. Eben Brown’s well across the road and a ten-quart pail and dipper were provided. Often the pail was lost in the well which necessitated the aid of some older person to fish it out with an eel spear.

Harold M. Crockett reflecting on school in the late 1800s, Our Island Town, 1941

We had no fancy lunch boxes with thermos bottles such as children have today but we carried our lunch in a pail…I’m sure when mother had to pack five or six “dinner pails” as we called them, she must have been very busy cooking, for we had mostly home cooking. People didn’t go to the store in those days and buy a loaf of bread, a can of tuna or peanut butter and a package of cookies for the lunch boxes as they do today…If we were fortunate enough to have a piece of pie that would be at the very top of the pail on a scallop shell.

Nettie Beverage Crockett, Personal recollection, 1966

While island schools had plumbing by 1925 and electricity in 1928, woodstove heat remained the norm into the 1930s. Samuel Beverage, who attended school at that time, remembered how on cold mornings the inkwells were placed on top of the school’s pot belly stove to thaw out. Occasionally the inkwell top would blow off, splattering ink on anything or anybody within range.

Nettie Beverage Crockett, Personal recollection, 1966

Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, school houses on North Haven were simple, one-room, single-story buildings, without electricity, plumbing, or central heat. A stove, fueled with wood from the pile outside, provided heat and students fetched drinking water from a local spring or well.

There was no sink, no water pipes, but we always had a water pail set out on the bench there, and there was a big dipper there that everybody drank out of.

Winnie Burgess Ames, Interview with Eliot Beveridge, circa 1980

The water supply came from Mr. Eben Brown’s well across the road and a ten-quart pail and dipper were provided. Often the pail was lost in the well which necessitated the aid of some older person to fish it out with an eel spear.

Harold M. Crockett reflecting on school in the late 1800s, Our Island Town, 1941

We had no fancy lunch boxes with thermos bottles such as children have today but we carried our lunch in a pail…I’m sure when mother had to pack five or six “dinner pails” as we called them, she must have been very busy cooking, for we had mostly home cooking. People didn’t go to the store in those days and buy a loaf of bread, a can of tuna or peanut butter and a package of cookies for the lunch boxes as they do today…If we were fortunate enough to have a piece of pie that would be at the very top of the pail on a scallop shell.

Nettie Beverage Crockett, Personal recollection, 1966

While island schools had plumbing by 1925 and electricity in 1928, woodstove heat remained the norm into the 1930s. Samuel Beverage, who attended school at that time, remembered how on cold mornings the inkwells were placed on top of the school’s pot belly stove to thaw out. Occasionally the inkwell top would blow off, splattering ink on anything or anybody within range.

Students sat together on benches and later at desks that held two or more children. Often, the seats and desks carried the names of former students, carved into the wood when the teacher's back was turned. In 1921, the island high school modernized seating arrangements by acquiring sixteen single adjustable seats and desks.

In early island schools, any textbooks were often owned by the students themselves. An 1889 state law required towns to provide textbooks in schools.

The free text book question is a somewhat serious one. It takes a comparatively large sum of money to keep up the present supply of books. We have had to buy quite a quantity of new and expensive books for the High School but it would be folly to put a workman into the field or shops without tools or even improper ones…We cannot afford to decrease the appropriation for text books.

Fremont Beverage, Superintendent of Schools, 1909

When the town was slow to supply funding for teaching aids such as maps or Victrolas, teachers often provided them or community members held events to raise the money. At the Northeast District School, a group of neighborhood women organized the “Northeast Circle” to help furnish such items as chairs, lamps, and even an organ.

Most island schools did not have playground equipment or an area for athletics. Children made use of the surrounding landscape to play games like tag or hide and seek and occasionally had use of a ball. The addition of simple swings to the school grounds provided endless entertainment.

I can picture in my mind our playground with one large rock, flat on top and with one side higher than the other making it just right for sitting on to eat our lunch. There were two other rocks about equal distance from the big one which we used as goals playing tag. Another game we played was hide and seek, using one corner of the schoolhouse for home base. As I recollect “hally over the schoolhouse” was a great favorite. Sides were chosen, places were taken on either side of the schoolhouse. The ball was thrown over the building and if it was caught the one catching it would run around the corner, followed by all the others and tag as many as possible before they turned the corner. All tagged would remain on that side. This would go on until all were captured for one side. Then the sides would be chosen all over again.

Nettie Beverage Crockett, Personal recollection, 1966

In early island schools, any textbooks were often owned by the students themselves. An 1889 state law required towns to provide textbooks in schools.

The free text book question is a somewhat serious one. It takes a comparatively large sum of money to keep up the present supply of books. We have had to buy quite a quantity of new and expensive books for the High School but it would be folly to put a workman into the field or shops without tools or even improper ones…We cannot afford to decrease the appropriation for text books.

Fremont Beverage, Superintendent of Schools, 1909

When the town was slow to supply funding for teaching aids such as maps or Victrolas, teachers often provided them or community members held events to raise the money. At the Northeast District School, a group of neighborhood women organized the “Northeast Circle” to help furnish such items as chairs, lamps, and even an organ.

Most island schools did not have playground equipment or an area for athletics. Children made use of the surrounding landscape to play games like tag or hide and seek and occasionally had use of a ball. The addition of simple swings to the school grounds provided endless entertainment.

I can picture in my mind our playground with one large rock, flat on top and with one side higher than the other making it just right for sitting on to eat our lunch. There were two other rocks about equal distance from the big one which we used as goals playing tag. Another game we played was hide and seek, using one corner of the schoolhouse for home base. As I recollect “hally over the schoolhouse” was a great favorite. Sides were chosen, places were taken on either side of the schoolhouse. The ball was thrown over the building and if it was caught the one catching it would run around the corner, followed by all the others and tag as many as possible before they turned the corner. All tagged would remain on that side. This would go on until all were captured for one side. Then the sides would be chosen all over again.

Nettie Beverage Crockett, Personal recollection, 1966

*Section title inspired by Eva Murray's book Island Schoolhouse: One Room for All, 2012